The Meiji Restoration and Japanese Historiography

Introduction

In the 19th century, the West’s colonial ambitions changed the face of Asia. European and U.S. desire for economic dominance of the region would bring about two centuries of war, exploitation, and resistance, both peaceful and violent. It would both disrupt and help to reshape the national identites of countries throughout the continent. Japan was not the first Asian nation to feel the force of Western colonialism, but they would be the first to take these threats, and resist through adaptation. Japan, unlike many of its neighbors, would never be colonized. Instead, it would embrace the mentality and methodology of the colonizer. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 would be a turning point in Japanese History, where the country rapidly modernized, and reassessed its role in the world. The study of history would play a key role in this process. Japanese historians would adopt historical theories and practices imported from Europe, and free their own past from Chinese cultural dominance. This new expression of Japanese history would build a nationalistic spirit that would push the once isolationist country beyond its coastal borders, in pursuit of its own colonial empire. The West had created a new rival in the East.

Japan and Historical Study Before the Restoration

Before the Restoration, Japan’s last major political upheaval took place in 1600. [Tokugawa Ieyasu’s] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokugawa_Ieyasu) victory against rival regional daimyo (warlords) at the Battle of Sekigahara in that year led to an era of political stability Japan had not seen for centuries. While the Yamato Dynasty, Japan’s Imperial Family, had, in theory, ruled uninterruptedly since the the 7th century, they had been little more than figureheads since the 12th century, when the first military ruler, known as a shogun, rose to power. Brief periods of stability would give way to eras of civil strife. Military leaders, would come close to unifying the land, but ultimately fall short. The Tokugawa would succeed where all others had failed. This period of peace and prosperity would see a flourishing of culture, commerce, literature and the arts.

The writing of history was no exception. The Tokugawa took great interest in history, funding various efforts to compile information about the recent past. While the output may have increased, the philosophy and methodology of history had changed little since the compiling of Japan’s earliest historical texts, the Kokiji and the Nihon Shoki in the 8th century. History was still written under the authority of the government, with the primary purpose to justify their rule. It was still written in Chinese, the preferred language of Japanese scholarship, and used classical Confucian methodology of evidence gathering, and document compilation. It was only in the twilight of the Tokugawa Period, when historians such as Motoori Norinaga and Rai Sanyo began to produce works that challenged those in power. Motoori’s study of the Kokiji put into question the validity of shogunate rule, which inspired Rai’s own Nihongaishi, a more directly critical take on the Tokugawa. (Borton 493-494)

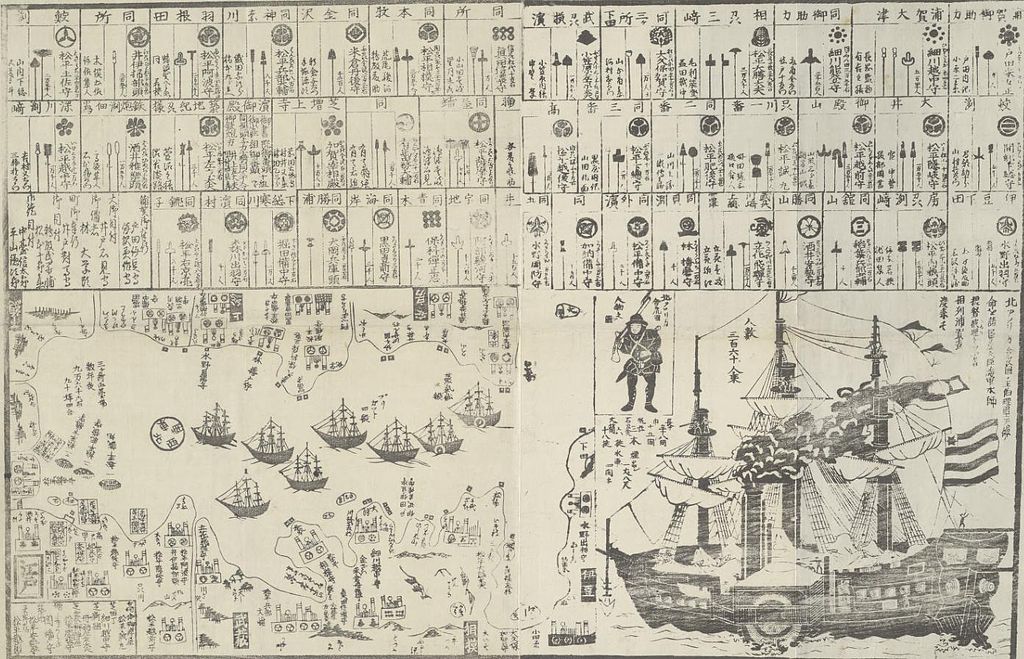

The Black Ships

In 1853, four U.S. Navy ships, commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry, entered Tokyo Bay. Perry’s orders were to demand that Japan end its 200 year old policy of global isolation, known as Sakoku and open itself to American trade. This act of gunboat diplomacy would not only have a profound impact on Japan, but on the entire world. In ten years, the Tokugawa Shogunate would fall, and the Emperor, for centuries merely a figurehead, would be reestablished as the center of the Japanese polity. In fifty years, the country would have so rapidly modernized, adapting to western ways of education, medicine, and war, that they were primed to to challenge the West for colonial dominance of Asia. Throughout this process, the way Japanese scholars viewed their past went through seismic shifts. Japan, and its history now had to be viewed through the lens of a larger world. Japanese scholars would study Western methods of historiography, synthesize them with more traditional models, and implement it to form the identity of a Japanese nation state.

The Restoration

The Tokugawa’s weak response to the aggressive trade demands of the United States, left an opening for a new power structure to emerge. This occurred in 1866, when the leaders of several feudal domains banded together, not to form their own shogunate, but to “restore” the current emperor to his rightful place of power. They succeeded in their efforts within two years, and the young Emperor Meiji took charge of the country. This “restoration” of Imperial power had great symbolic meaning. If Japan was to deal with the arrival of the West, it must modernize, but it also must not lose its identity. What better protector of the past than a man whose lineage dates back to mythical Japanese rulers dating back thousands of years? As Japan moved to shed its isolationist past, it would even more closely hold on to its history.

Fukuzawa Yuichi and Japanese Civilization

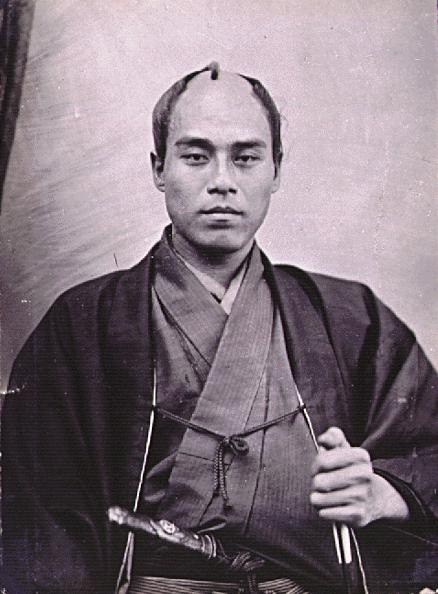

Fukuzawa Yuichi, was perhaps Japan’s most famous 19th century philosopher, so much so that his face currently resides on the 10,000 yen note. Fukuzawa’s work, which crossed over from the Tokugawa to the Meiji Period, focused on Western learning, and how it could be used to benefit Japan. While much of his focus was on education, an interest which lead to his founding of Keio University, the first university in Japan to use western methods, he did engage in the philosophy of history. His work *An Outline of a Theory of Civilization**, influenced by the work of British historian Henry Thomas Buckle, would similarly focus on history as the story of civilizations (Fukuzawa 19). The final chapters of the book contrast the origins of Western and Japanese civilizations, finding the later presently at a disadvantage. This acceptance of the West’s current “superior” civilization was a prime motivator for Fukuzawa, and the Meiji era as a whole. The West was to be emulated, but only for the advancement of Japanese “civilization.” This movement would have no greater advocate than the Emperor himself.

The Founding of Historiographical Bureau

In 1869, at the beginning of the Restoration, the following Imperial rescript was posted:

Historiography is a for ever immortal state ritual (taiten) and a wonderful act of our ancestors. But after the Six National Histories it was interrupted and no longer continued… Therefore we wish that an office of historiography (shikyoku) be established, that the good custom of our ancestors be resumed and that the knowledge and education be spread throughout the land… Let us set right the relations between monarch and subject, distinguish clearly between the alien and proper (ka’i naigai) and implant virtue throughout our land. (Mehl 227)

This declaration of the importance of historiography so early in the reign of an new government, reveals the value of history, or more specifically the control of historical narrative, to the legitimacy of rule. Thus the Historical Bureau was founded. The bureau was incorporated into Tokyo Imperial University in 1888, eventually being renamed the Historiographical Institute in 1929, the name in which it functions under today. The early work of these scholars was more in line with archivists than historians, compiling a massive amount of primary source material, which would be collected in works such as the Fuken shiryo. The organization’s deputy director, Shigeno Yasutsugu, was one of Japan’s earliest, and most influential historians. While Shigeno, and other’s working for the Bureau, were well read when it came to the “new” historical methods being developed by Leopold von Ranke they were still very much ensconced in their Confucian historical tradition. This does not mean that they did not adhere to a primary source-based method of historical study. Shigeno, and fellow important Confucian scholar within the Bureau, Kume Kunitake “set out to free Japanese history from the myths that dominated the treatment of antiquity”, even goings as far as disproving the existence of several famous historical figures. (Jansen 483-484)

History and the State

Kume’s elevated status at the Imperial University was short-lived. In 1892, he wrote an article that would immediately cast him out of favor with Imperial authorities. Shinto Is an Outdated Custom of Heaven Worship was a powerful critique of the very state-sponsored religion that the Imperial Household was using to maintain its legitimacy, calling into question their historical descendance from Amaterasu, the sun goddess, and most important figure in Shinto mythology. While Kume was able to able to continue writing, and eventually found work a private university, he was finished at the Historiographical Bureau. That none of his colleagues stood up for him was a sign of things to come, as State Shinto, traditional Japanese spirituality co-opted by the nation’s new leaders, grew in influence during the 20th century.

This would not turn out to be an isolated incident, though the government would prefer the use of soft power over the country’s intellectuals. Often, these historians would be employees of the government itself, such as members of the Historical Bureau, or independently wrapped up in the nationalistic fever of the moment. When the government felt it was important enough, such as a troubling, from the perspective of royal legitimacy, period in the the 14th century where there were two Imperial Households, they would merely dictate what historians were allowed write. (Jansen 486)

The Liberation of Western Influence

The influence of Western historiography was most evident in the appearance of Ludwig Riess a student of Ranke, at Tokyo Imperial University. Riess taught history, and promoted new methods of historical science. He was instrumental in introducing Western sources to the study of Japanese history. While Riess’ work in Japan, which lasted until 1903, was important, it had significantly less impact than Japanese historians’ own transformations of Western historiographical ideas. (Mehl 232) Another German living in Japan, a physician named Erwin Balz, was told by a Japanese student “We have no history” and that “our history begins today” (Jansen 460). This was spirit of te Meiji Restoration. The country would take what the West had to offer, and create a “new” Japan on its own terms.

The ability to incorporate Western Historiography into their own methodology, allowed Japanese historians to create a sense of unique Japanese identity, not burdened by the cultural and historiographical inheritance of China. (Popkin 86) For centuries, Japan had adopted, and adapted, Chinese religious, political, and cultural practices. By the mid-19th century, China, devastated by civil war, and twice defeated by the British during the Opium Wars was no longer a model that Japan wished to emulate. The fear of a similar defeat to the forces of Western colonialism is what led to the Restoration itself. Instead of accepting the physical and economic colonialism forced upon China, Japan would embrace the ideas and methods of these would-be colonizers. The nationalistic trends in 19th century European historiography were embraced by Japanese scholars. The shoguns and daimyo, so recently ousted from power, would now become symbols of a unique Japanese national identity.

Heroes of the Past

Independent historians, such as Yamaji Aizan, worked outside the influence of the Historiographical Bureau, embracing the mythology men like Shigeno sought to debunk. Yamaji’s populistic beliefs led him to promote the ideas of individual agency, and the powerful role of the hero in nation building. These ideas were inspired by the work of Thomas Carlyle a 19th century Scottish philosopher and historian, who was an early advocate of the Great Man Theory of history. His work, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History, was one of many western texts translated into Japanese during the later half of the 19th century. Yamaji embraced these heroic ideals, and wrote quasi-fictional biographies of “great men” throughout Japanese history. Powerful shoguns, such as Minamoto Yoritomo, Ashikaga Takauji and even the founder of the so recently deposed Tokugawa Shogunate, were represented as civilizing heroes. The inclusion of Saigō Takamori, one of the founders of the Restoration, who eventually rejected the westernization of the military, and led the failed Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, reveals how rapidly the mythologizing process was taking place. Yamaji’s advocacy of Japan’s Imperial ambitions led to a unifying of all Japanese heroes, though none had ever fought for the nation state that had emerged from the Restoration. (Karlin 76-77) The legacies of these men, so recently crafted by historians, would soon be invoked by Japanese soldiers on battlefields throughout the Asian continent.

Conclusion: Japan on the World’s Stage

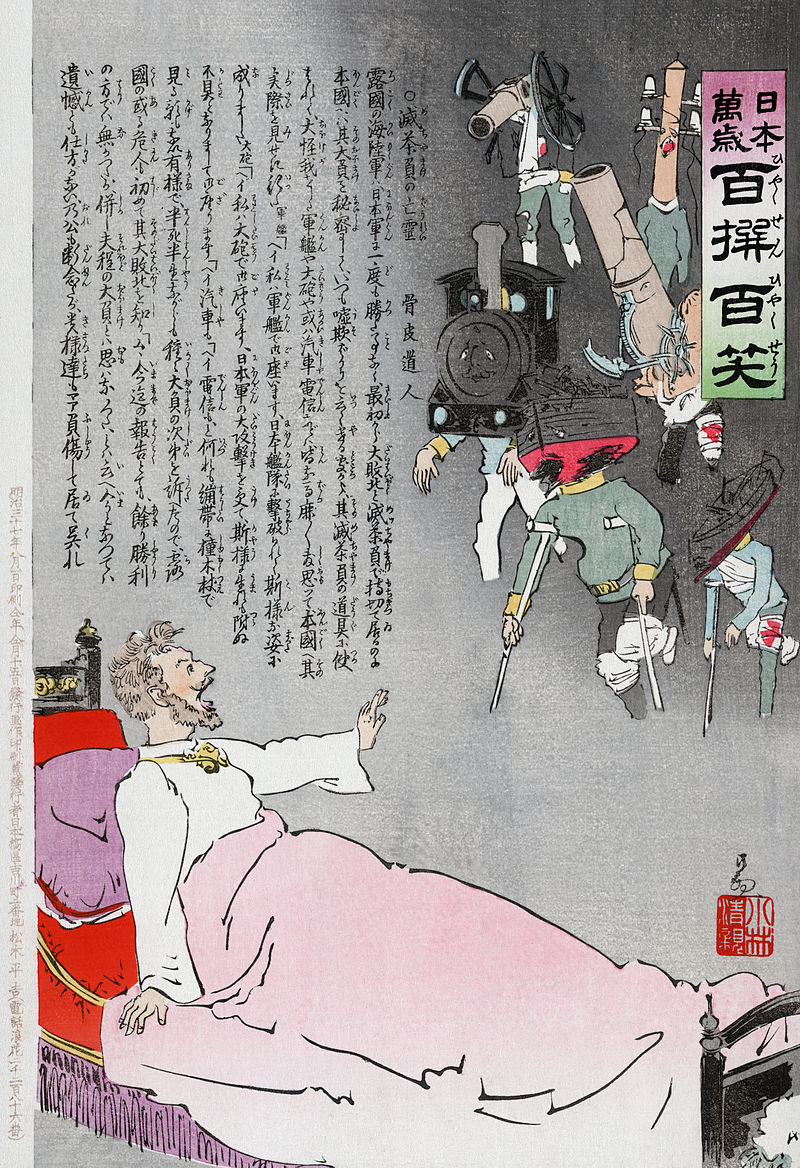

The new Japanese nationalistic spirit would first manifest in violence at the close of the 19th century. The era would be marked by a series of military victories what would make manifest Japan’s new historical vision of itself. The First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 revealed, in sharp contrast, the success of Japanese modernization efforts, and the failures of the Chinese Qing Dynasty’s similar drive towards modernity. That dynasty, which had ruled for as long as the Tokugawa, would collapse in the following decade, leaving China, the once great hegemon of Asia, fragmented for years to come. Japan stepped into that void, colonizing Korea, Taiwan (then Formosa), Manchuria, and, eventually, the majority of Western colonial holdings in East and Southeast Asia. The first of these colonial powers to fall would be Russia. Their defeat at the hands of the Japanese in 1905 exposed not only their own weakness, but the failing grip of European colonialism. Japan not only took Western technology, but 19th century Western ideas of national identity, born out of historiographical concepts, and formed a new order in the East.

Bibliography

Borton, Hugh. “A Survey of Japanese Historiography.” In The American Historical Review Vol. 43, No. 3: 489-499. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1865611

Fukuzawa, Yukichi. An Outline of a Theory of Civilization. Translated by David A. Dilworth and G. Cameron Hurst. Tokyo: Sophia University, 1973.

Jansen, Marius B. The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2000.

Karlin, Jason G. Gender and Nation in Meiji Japan: Modernity, Loss, and the Doing of History. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014.

Mehl, Margaret. “German Influence on Historical Scholarship in Meiji Japan.” In Japanese Civilization in the Modern World No. 16: 225–246.

Popkin, Jeremy D. “The 19th Century and the Rise of Academic Scholarship.” In From Herodotus to H-Net: The Story of Historiography. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

2575 words.